Istanbul transcends eras, empires, architecture, art, religions, and even continents. From early pre-Roman Greek settlers, to the Roman Empire, to the Byzantine Empire, to the Ottoman Empire and now to the dynamic Republic of Turkey, Istanbul has seen the waves of history continually wash over it. The city served as an imperial capital for almost 1600 years: during the Byzantine (330–1204), Latin (1204–1261), late Byzantine (1261–1453), and Ottoman (1453–1922) empires. The city grew in size and influence, eventually becoming a beacon of the Silk Road and one of the most important cities in history.

It is now an incredibly clean, safe, diverse, dynamic modern city with a world class transportation system. At over 15 million people it is the largest city in Europe. As you can imagine, there is a lot to see and experience in this magnificent city, and the length and diversity of this post reflects that.

Whirling Dervishes

Before delving into Istanbul’s vast history, here is one of it’s most unique current experiences.

Sufi whirling is a form of physically active meditation which originated among certain Sufi groups, and which is still practiced by the Sufi Dervishes of the Mevlevi order. It is a customary meditation practice performed within the sema, or worship ceremony, through which dervishes aim to reach greater connection with Allah. This is sought through abandoning one’s nafs, ego or personal desires, by listening to the music, focusing on God, and spinning one’s body in repetitive circles.

This wonderful video describes some of what the experience is like for the Dervishes.

I was able to go to one of these ceremonies while I was in Istanbul. The entire ceremony was about an hour long. Most of it was composed of simple, beautiful music. The Dervishes only performed for a small part of the overall time, but it was still a very nice, peaceful experience to see.

They start out a bit slow to get in synch with the music.

And then they get in synch and whirl around in their trances.

Hagia Sophia

Hagia Sophia is the epitome of Istanbul’s history. For a thousand years, it served as the greatest church in Christendom. It was home to the Byzantine Emperor and Orthodox Patriarch, and a beacon of civilization during Western Europe’s dark ages. When Muslims conquered Constantinople, this huge church suddenly became one of the world’s greatest mosques.

The church was built between AD 532 and 537, in the waning days of the Roman Empire by Justinian I, the last great Roman emperor. Constantinople was the empire’s capital, as the city of Rome had fallen to barbarians. By building Hagia Sophia, Justinian was sending a message to the world that the grandeur of Rome would continue for centuries to come.

He envisioned a church of mind-boggling proportions. He spared no expense. Some 10,000 architects, stonemasons, bricklayers, plasterers, sculptors, painters, and mosaic artists worked around the clock. Hagia Sophia became an instant legend. For a while, it was the biggest building in the world. It would remain the biggest cathedral for nearly a thousand years. With a footprint of over 60,000 square feet, it could host nearly 20,000 worshippers. Justinian’s church surpassed even St. Peter’s in Rome.

The mosaics are from Justinian’s day. The ceiling is an elaborate pattern of squares, circles, and arches.

The dome was the central element in the church’s groundbreaking design. Placing a round dome atop a square building seems simple, but at the time, it was revolutionary. In fact, having a square church at all was unheard of in the Christian world, where basilicas were always long, narrow, and low-ceilinged.

On either side of the nave are enormous 45-foot-tall columns of speckled-green marble topped with lacy white capitals. These big columns are matched by smaller ones midway up in the gallery. Each column was quarried in Greece, dragged to a port, shipped across the Aegean, transported to this site, and erected in place, using ropes and pulleys and scores of workers.

Topkapı Palace

For centuries, this was the primary palace of the Ottoman Empire. Built on the remains of ancient Byzantium, Mehmet II established this palace as an administrative headquarters and royal residence. The palace grounds includes a 16th century kitchen, 10,000 pieces of fine Chinese porcelain, traditional weapons, royal robes, ceremonial thrones, and Sultan Ahmet III’s tulip garden.

The Divan was where the sultan and his advisors met four times a week to dictate the laws governing the lives of over 30 million people.

The armory building now contains a collection of the sultans’ personaly weaponry.

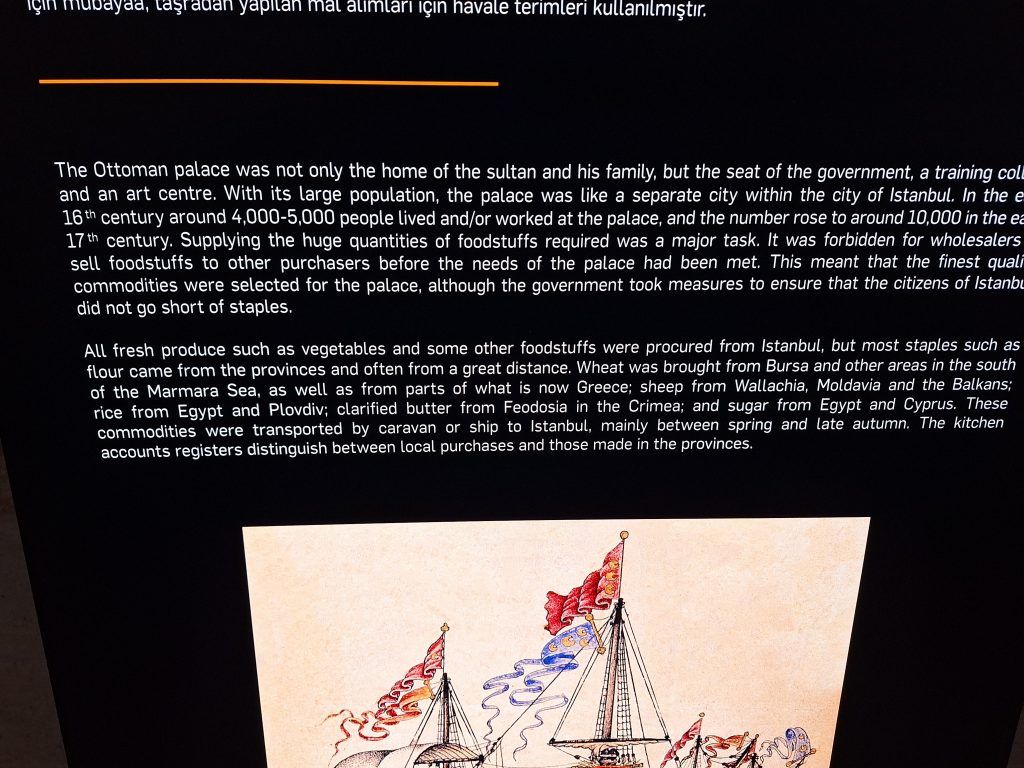

A description of the scale of the palace and the logistics of feeding everyone.

The Gate of Felicity separated the public area of the palace grounds from the sultan’s private realm.

The sultan’s private library is a light, airy building.

The views of the Bosphorus from the sultan’s gardens.

What was once the treasury building now holds some of the most valuable items of the Ottoman Empire, including gifts from other rulers…

…and the famous Topkapi Dagger. Its hilt is studded by huge emeralds and surrounded by diamonds and gold.

The Blue Mosque

The Blue Mosque was constructed between 1609 and 1617 during the rule of Ahmed I. The mosque has a classical Ottoman layout with a central dome surrounded by four semi-domes over the prayer hall. It is fronted by a large courtyard and flanked by six minarets. On the inside it is decorated with thousands of Iznik tiles and painted floral motifs in predominantly blue colours, which give the mosque its popular name.

The Blue Mosque represents the pinnacle of Ottoman architecture. It also marks the beginning of the empire’s decline. Thanks to the enormous cost of its construction, the treasury was exhausted, the Ottoman Empire became stagnant, and never again would they build a mosque of such splendor.

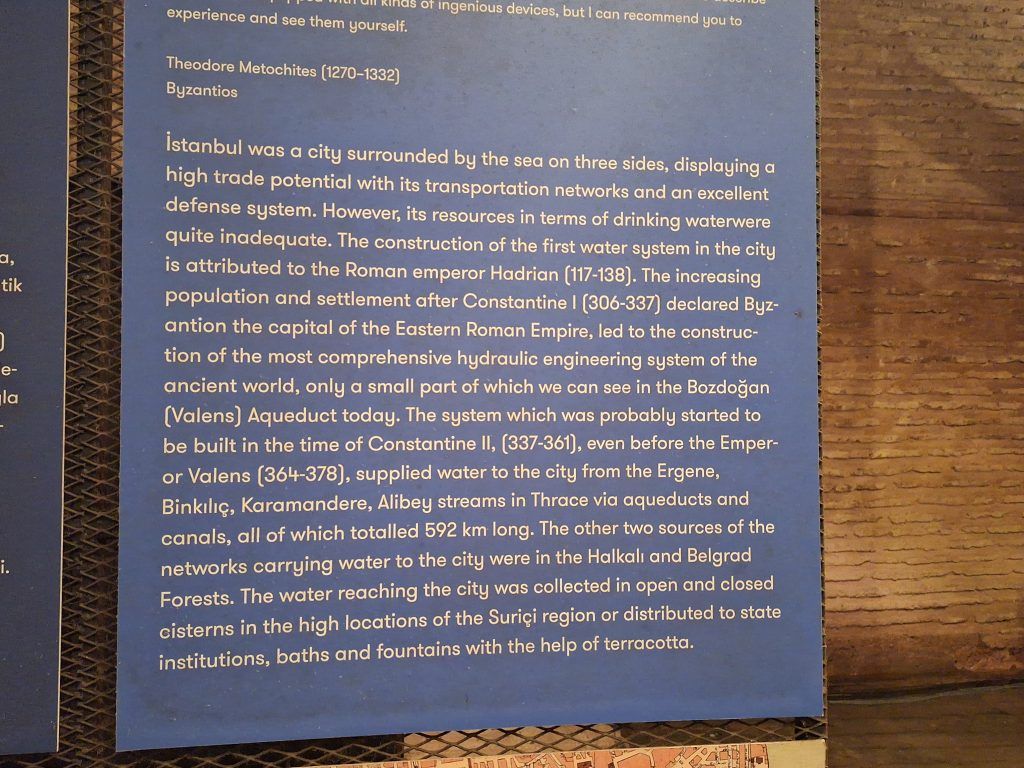

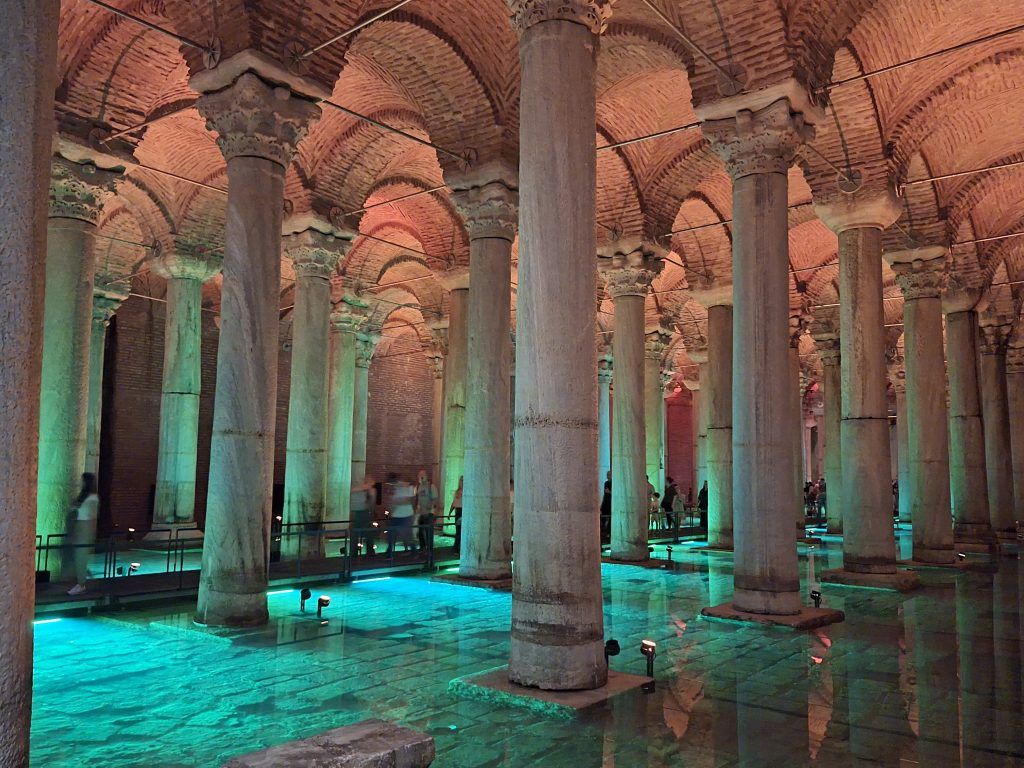

Basilica Cistern

The Basilica Cistern was built 1,500 years ago by Emperor Justinian; the same man who built Hagia Sophia. Over 7,000 slaves labored on the project. This was the city’s largest cistern. It was just one cistern of hundreds in the city’s vast water supply system. Fresh water from 10 miles away was channeled here through underground pipes and across raised aqueducts.

It’s 150 yards long and 70 yards wide. A forest of 336 columns supports the cross-vaulted brick ceiling. The walls are four feet thick. In its day, the cistern was completely filled with fresh water. It could hold more than 20 million gallons to serve the daily needs of 100,000 Byzantines.

Bosphorus Straight Cruise

The Bosphorus Strait is a 19 mile long waterway that connects the Black Sea with the Sea of Marmara (which, at its western end, flows through the Dardanelles to the Aegean Sea, and then out to the Mediterranean Sea). The great commercial and strategic importance of the Bosphorus was a factor in the establishment of the city of Constantinople here in AD 330.

In addition to separating two continents, the Bosphorus Strait serves as Istanbul’s main highway. A never-ending stream of vessels – from little fishing dinghies to gigantic rusted oil tankers to luxury cruise ships – sail up and down this strategic corridor, day in and day out. The Bosphorus is one of the busiest waterways in the world; it is the only outlet to the Mediterranean for Russia, and the only route to any sea for the other countries on the Black Sea: Romania, Bulgaria, Ukraine, and Georgia.

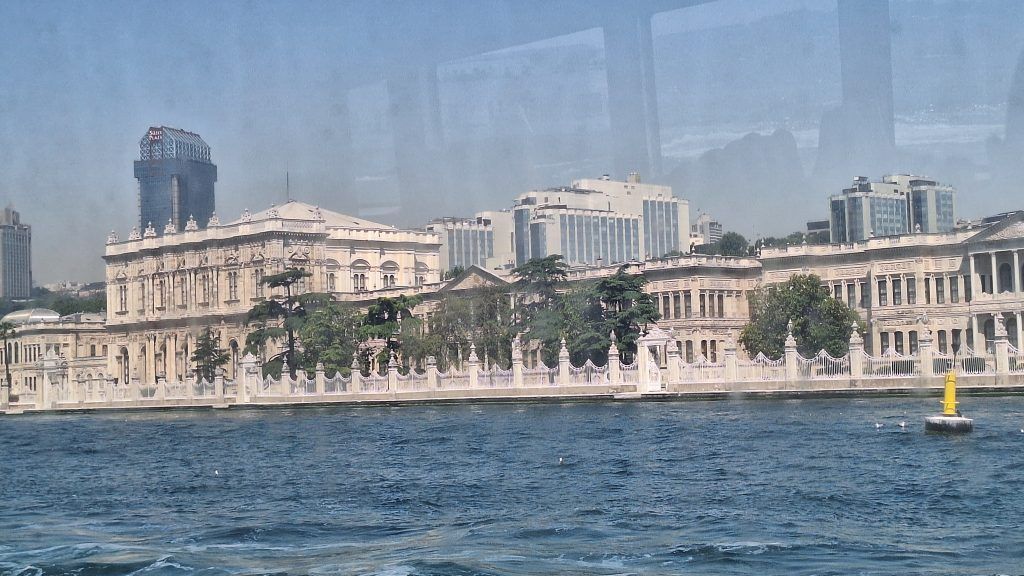

I took the public cruise which took about 2 hours to traverse the Strait. I had a choice of sitting on the crowded top deck, where I could get great pictures but have no sun protection, or down in the much sparcely crowded enclosed deck where I could relax in the cool air conditioning, but take subpar pictures through the dirty windows. I chose the latter option, so please excuse the reflections and dirt on some of these pictures.

Below are the Dolmabahce Palace on the European side, the waterfront at Uskadar on the Asian side, and an unidentified adminstrative building on the European side.

The Bosphorus Bridge is the first bridge we passed. It is the first of three suspension bridges over the Bosphorus. A Turkish-British corporation completed the span in 1973, on the 50th anniversary of the Turkish Republic. Almost two-thirds of a mile long, it carries six lanes of traffic between the continents. The area around it on the European side is called Ortakoy.

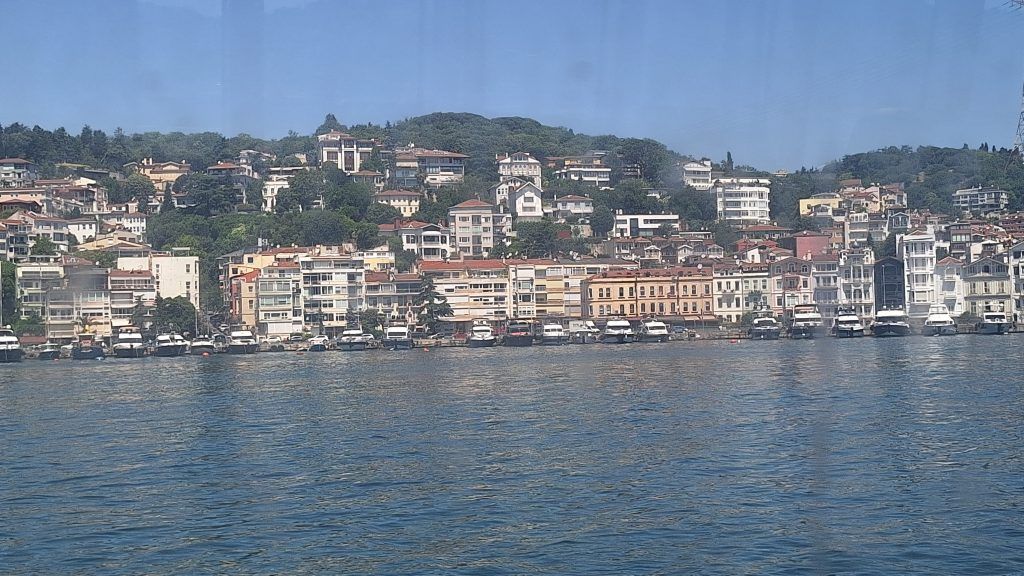

The wealthy, relaxed European side enclave of Bebek.

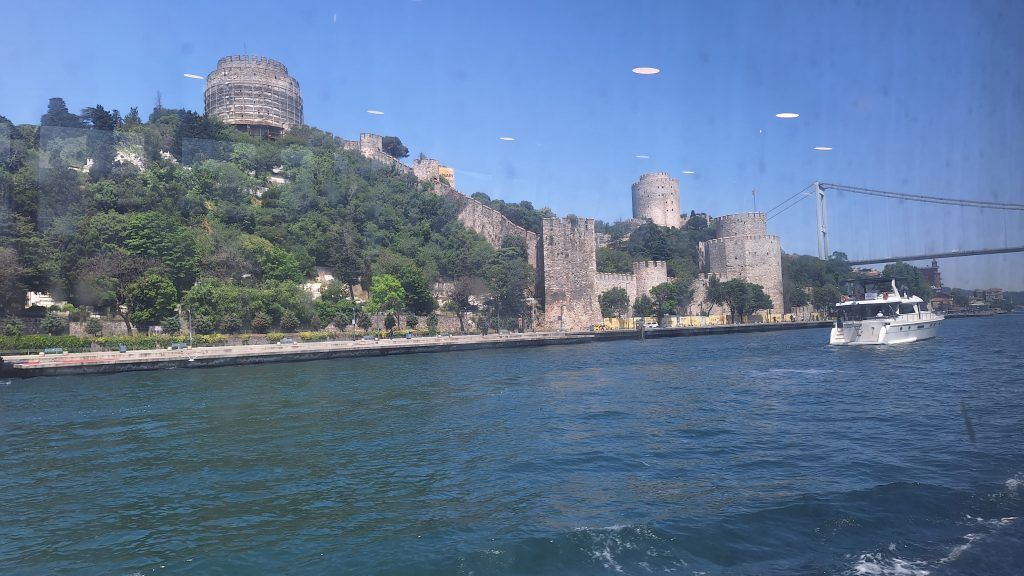

The Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge was completed in 1988 and was the 5th longest suspension bridge in the world. Just before the bridge is the Rumeli Fortress that was conceived and built between 1451 and 1452 on the orders of Sultan Mehmed II. It was commissioned in preparation for a planned Ottoman siege on the then-Byzantine city of Constantinople, with the goal of cutting off maritime military and logistical relief that could potentially come to the Byzantines’ aid by way of the Bosphorus Strait

One of the many large ships we passed by on the cruise. This was on the way out, where I had this whole area almost to myself. On the way back a lot of the people that had been on the top deck decided to sit below and it was more crowded.

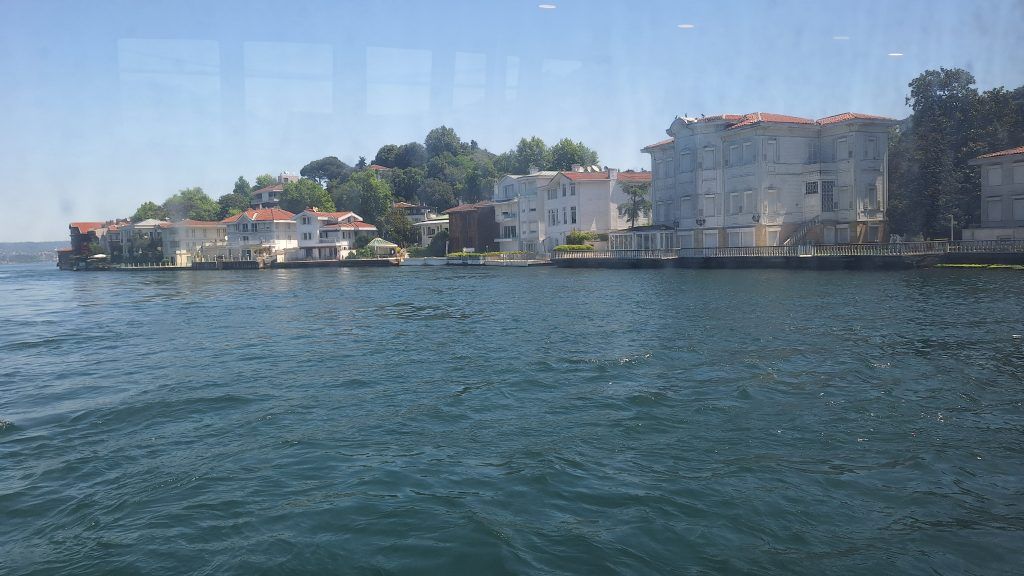

Some of the luxury homes on the Asian side.

This area on the European side have some extremely dangerous hidden rocks that have long plagued navigators. In the tale of Jason and the Argonauts, the crew encountered the Clashing Rocks as they sailed into the Black Sea. These rocks of legend are believed by some to be based on this stretch of the Bosphorus. Byzantine emperors erected a huge column here to warn passing ships. It worked…except when thick fog made this part of the Bosphorus nearly impossible to navigate. It’s still difficult today, even with state-of-the-art electronic equipment.

We stopped for a couple of hours at the small fishing village of Anadolu Kavağı on the Asian side. Anadolu comes from the Greek word anatoli, meaning “the land to the East,” while kavak means “controlled pass.” From Byzantine times to the present, this has been a strategic checkpoint for vessels going through the Bosphorus.

I climbed up to the ruins of the Yoros Castle. From Wikipedia, you can see that this castle has had a dramatic history:

“Yoros Castle was intermittently occupied throughout the course of the Byzantine Empire. Under the Palaiologos dynasty in its later years, Yoros Castle was strongly fortified, as was the castle on the opposite side of the Bosphorus. A massive chain could be extended between these two points, cutting the Strait off from enemy warships in the same way that the chain across the Golden Horn was used to defend Constantinople during the last Ottoman siege by Sultan Mehmed II.

The Byzantines, Genoese and Ottomans fought over this castle for centuries. It was first captured by Ottoman forces in 1305, but was retaken by the Byzantines shortly afterwards. Sultan Bayezid I took the castle again in 1391 while preparing for his siege of Constantinople, and it was used as a base during the construction of Anadolu Hisarı, which was to prove more important in the eventual successful siege. In 1399 the Byzantines attempted to take back Yoros Castle. The attack failed, but the village of Anadolu Kavağı was burned to the ground. The Ottomans held the fortress from 1391–1414, losing it to the Genoese in 1414. Their forty-year occupation gave the castle its commonly used nickname – the Genoese Castle.

After Sultan Mehmed II’s conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the presence of the Genoese in such a strategic location posed a threat to the new Ottoman capital and within a few years they were driven out. Mehmed II then refortified the walls, and constructed a customs office, a quarantine centre and a check point, as well as garrisoning the site. Cossack raids plagued the Ottoman Empire from time to time. In 1624 a fleet of 150 Cossack caiques sailed across the Black Sea to attack Bosphorus towns and villages. Sultan Murad IV (1623–1640) refortified Anadolu Kavağı as a defence against them. This proved instrumental in securing the region against such seaborne raids. Under Osman III (1754–1757), Yoros Castle was once again refortified. Later, in 1783 Abdülhamid I added more watchtowers. After this time, the castle gradually fell into disrepair. By the time the Turkish Republic was declared in 1923, it was no longer in use.”

There was a film shoot going on the day I visited. They kept trying to herd the tourists to one side as they tried to film a scene. It was for a popular joint Turkish-Iranian TV show.

The Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge was complted in 2016. At 322 m (1,056 ft), it is the world’s fifth-tallest bridge of any type. The main span is the 13th longest suspension bridge in the world. It is also one of the world’s widest suspension bridges, at 58.4 metres (192 ft) across. It’s the primary international transportation road between this part of the Black Sea. It’s only one of the three Bosphorus bridges that allows trucks.

Behind the bridge is the Black Sea. The Asian side is on the right and the European side is on the left.

Looking across to the European side and the strong currents on this part of the Straight.

Looking down on the town with our ferry boat parked at the small dock.

This very simple map shows the strategic value of this small body of water.

Chora Church

The Chora Church was originally built in the early 4th century as part of a monastery complex. It was rebuilt in the 14th century after some of the walls collapsed, possibly due to an earthquake. The intricate decorations that this church is known for were created between 1310 and 1317. The Chora’s art was ahead of its time, and in a way anticipated the Renaissance: art for the sake of religion, but without neglecting aesthetics.

After the Church split between east and west (Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic) in the 11th century, Western churches became provincial, focused on their own local customs and saints—with church art that splintered into many different, idiosyncratic visions. Meanwhile, the Eastern Orthodox Church remained consolidated under the stable and wealthy Byzantine Empire. Church power was centralized, so artistic decisions made in Constantinople filtered down to churches throughout the Byzantine world, bringing consistency to medieval church decorations. The artistic vision realized here in the Chora eventually trickled down to decorations in today’s Christian churches in places like Italy, Indonesia, and the US.

In the early 16th century, 60 years after the Ottomans took Constantinople, the church was converted into a mosque. A mihrab (prayer niche) was built off-center in the main apse (to face Mecca), and the bell tower was replaced with the minaret you see today. The Byzantine-era frescoes and mosaics were whitewashed over and remained hidden from daylight until the late 1940s, when they were rediscovered and restored.

As you can see in the pictures below these 700 year old intricate mosaic images are still incredibly beautiful.

Mosque of Suleyman the Magnificent

Built for the sultan by his prolific architect, Sinan, and completed in 1557, the Mosque of Suleyman the Magnificent almost outdoes the Blue Mosque in its sheer size, architecture, and design. Its subtly understated interior is decorated in pastel tones. It creates a very tranquil setting.

The architect behind this building—whom Turks call “Sinan the Great”—struggled his whole life to engineer a single dome that could span an entire building, without bulky support arches and pillars. He considered this mosque an important milestone in his quest.

The impressive dome (flanked by two semi-domes, as at Hagia Sophia) has a diameter of 90 feet. While Renaissance architects in Europe were struggling to sort out the basic technical difficulties of building domes, Sinan succeeded in creating an elegant, masterful dome that included such details as open earthenware jars embedded between the brick layers to enhance acoustics.

Grand Bazaar

The world’s oldest shopping mall is a huge labyrinthine of shops, aggressive shopkeepers and hordes of tourists. The construction of the core started during the winter of 1455, shortly after the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople, and was part of a broader initiative to stimulate economic prosperity in Istanbul. At the beginning of the 17th century the Grand Bazaar had already achieved its final shape. The enormous extent of the Ottoman Empire in three continents, and the total control of road communications between Asia and Europe, rendered the Bazaar and the surrounding area the hub of the Mediterranean trade. According to several European travelers, at that time, and until the first half of the 19th century, the market was unrivaled in Europe with regards to the abundance, variety and quality of the goods on sale.

It currently has 61 covered streets and over 4,000 shops on a total area of 30,700 square meters attracting between 250,000 and 400,000 visitors daily, and employing over 26,000 people.

Hagia Irene

Hagis Irene is the first church completed in Constantinople, before Hagia Sophia, during its transformation from a Greek trading colony to the eastern capital of the Roman Empire. The Roman emperor Constantine I commissioned this and it was completed by the end of his reign (337). During the Nika revolt in 532, Hagia Irene was burned down. In the wake of the riots, Emperor Justinian I, who had almost been deposed during the riot, had the church rebuilt in 548 as part of a widespread architectural project.

Hagia Irene hosted the Second Ecumenical Council to set the course for the new church (in AD 381). Decisions made in this building shaped Christian traditions for centuries to come. In the short term, the council—which discussed theological questions such as whether Jesus was human, divine, or both—sparked social struggles and riots in the early history of the capital. Hagia Irene served as the patriarchal church of Constantinople until Hagia Sophia was built.

Under Ottoman rule, Hagia Irene was used as an arsenal by the imperial guards and later to store artifacts from the Istanbul Archaeological Museums.

Church of St. George and The Greek Orthodox Patriarchate

This unassuming complex holds the modern offices of the head of the Greek Orthodox Church and its roughly 300 million followers worldwide. The Patriarchate in Istanbul is as important to followers of the Orthodox faith as the Vatican in Rome is to Catholics.

Hagia Sophia was the seat of the patriarch until the Ottoman conquest in 1453. After that, the Patriarchate moved to several different locations before finally finding a permanent home here in the Fener neighborhood in the early 1600s, making this the center of Greek Orthodox life in the city. The name “Fener” is often used as a nickname for the Patriarchate, just as the name “Vatican” is used as shorthand for the leaders of the Catholic Church. Though only a couple of thousand Greek Orthodox Christians reside in Istanbul today, the Greek Orthodox Church remains very influential here.

St. George Church is the church within the Patriarchate. It is the Orthodox Church’s much, much more modest version of St. Peter’s Basilica. This church has had a long connection with the Patriarchate of Jerusalem. Every year, on April 23, the patriarch of Jerusalem and the Ecumenical Greek Orthodox patriarch hold a special joint service here, conducted in three languages: Arabic, Greek, and Turkish.

Lonca and Balat Neighborhoods

Long ago, Istanbul’s Roma (Gypsy) families, wearied of traveling, settled in the neighborhoods of Lonca and Balat. Laundry hanging from lines stretched across the street; young children running around, hollering for attention; and elderly women sitting out on doorsteps, chatting and sipping tea; these are common scenes in the alleyways of Lonca

Until the 1950s, Balat was a bustling Jewish neighborhood with a lively market. Over time many Jewish people who could afford it have moved to more desirable neighborhoods elsewhere in Istanbul. Today’s Balat is missing the taverns, jewelers, fabric merchants, and bankers of the past. They’ve been replaced by hardware stores, metal repair shops, butchers, wholesalers, and green grocers.

Thanks to a European Union project, Balat has had a facelift in recent years. With many of its once-dilapidated buildings restored, the neighborhood is evolving into a trendy design district, with a smattering of artists’ studios and craft workshops.

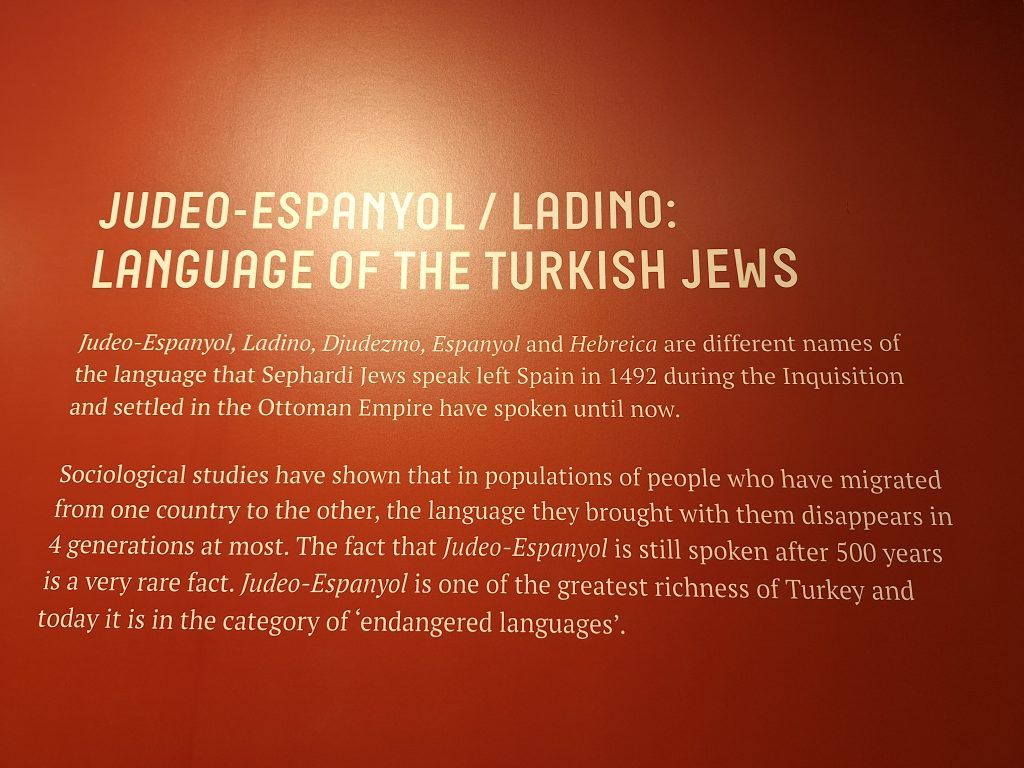

Quincentennial Museum of Turkish Jews

Jews arrived in what is now Turkey between the sixth century BCE and 133 BCE, when the Romans arrived. They were Romaniote Jews and first settled in Phrygia and Lydia.

In 1492, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabel of Spain ordered their Sephardic Jewish population to accept the Christian faith or leave and “dare not return.” The Ottoman sultan Beyazıt Han was the only monarch of the time who extended an invitation to take in these refugees. By the end of the sixteenth century, the Jewish population in the Ottoman Empire was over 150,000 and was the largest Jewish community in the world.

The Quincentennial Foundation was established in 1989 by 113 Turkish citizens, Jews and Muslims alike, to celebrate the five hundredth anniversary of the arrival of Sephardim to the Ottoman Empire. This museum commemorates those first Sephardic Jews who found a new home here. The building was an early 19th century synagogue built on the remains of a much older synagogue; now it displays items donated by the local Jewish community. Today, Turkey’s Jewish community is estimated at 25,000 people, about 95 percent of whom are descendants of those Spanish exiles.

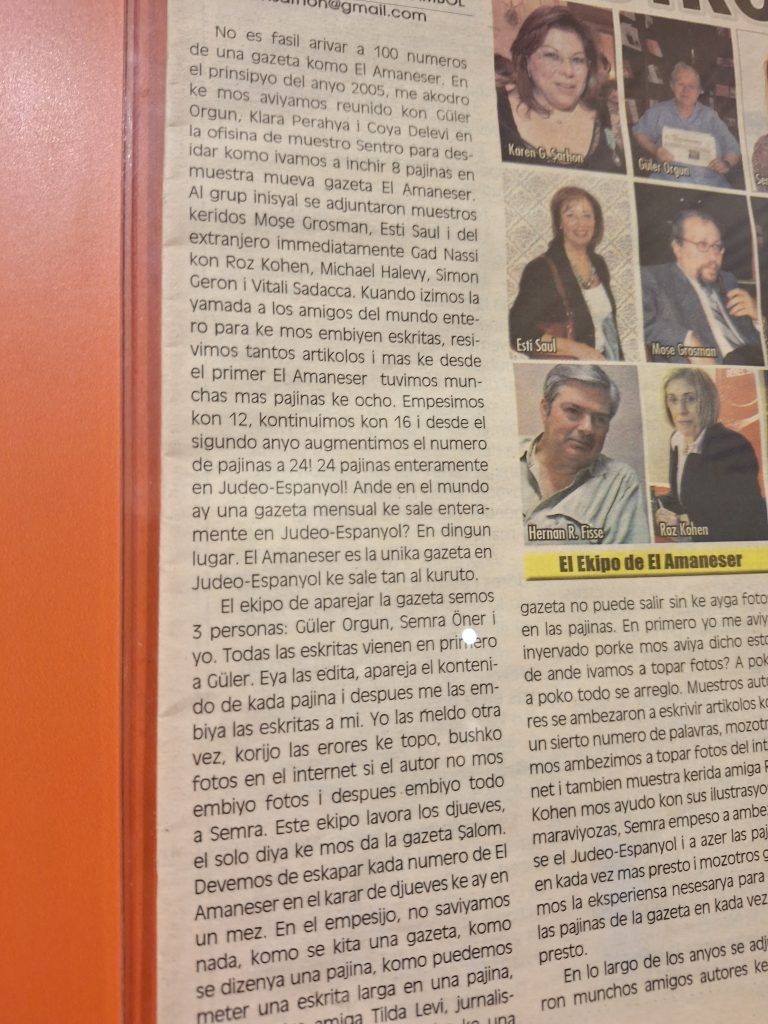

It’s interesting to see the strong influence of the Spanish language on the Turkish Jews.

If you speak Spanish you can probably understand much of what is said in this newspaper article.

The synagogue housed within the museum.

St. Anthony’s Roman Catholic Church

St. Anthony’s was completed in 1912 by the city’s Italian community (mostly made up of people of Genoese and Venetian descent). Franciscan priests first built a church here in the 13th century. Pope John XXIII preached here for 10 years while he was the Vatican’s ambassador to Turkey before being chosen as pope. He is known as “the Turkish Pope” because of his fluency in Turkish and his oft-expressed love for Turkey and for Istanbul in particular. St. Anthony’s still serves an active Roman Catholic congregation with weekly Mass, and the Christmas service here has become a major social event in Istanbul, attended by Turkey’s jet set (even many Muslims).

Karakoy District

In Byzantine times, this area was inhabited by commercial colonies of Genoese and Venetian settlers. In the late Ottoman era, it became a residential area for non-Muslims, including Jews, Catholics, and Eastern Orthodox Christians. Today, this part of the city is dominated by the famous Galata Tower. The area has been the scene of an extensive rebuilding project, as rundown buildings make way for art galleries, deluxe hotels, and convention centers.

There is a really nice promenade here along the Bosphorus.

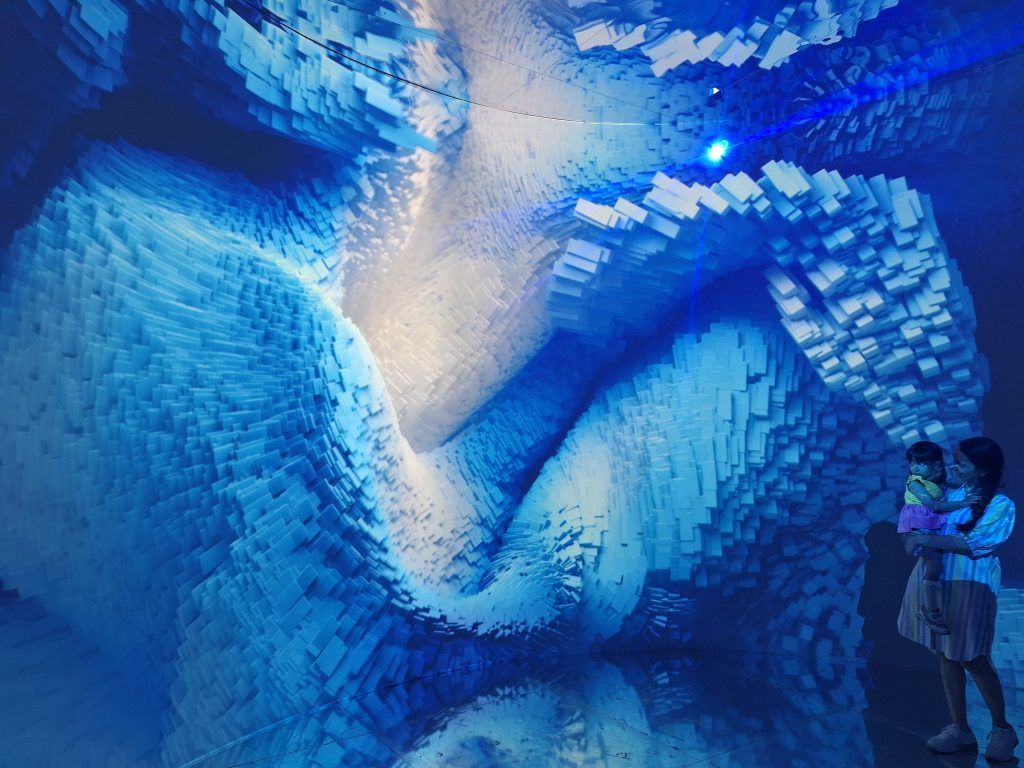

In 2004 Istanbul Modern became Turkey’s first modern and contemporary art gallery focusing on Turkish artists.

While I was filming this unique exhibit I was told I was only allowed to take pictures, not film. So I wasn’t able to show the rest of this. But it’s still pretty unique; it’s basically a large painting hanging from the ceiling with parts of it being a film.

This water exhibit was right next door. I snuck in a short video before the guard came in. It’s a really unique experience.

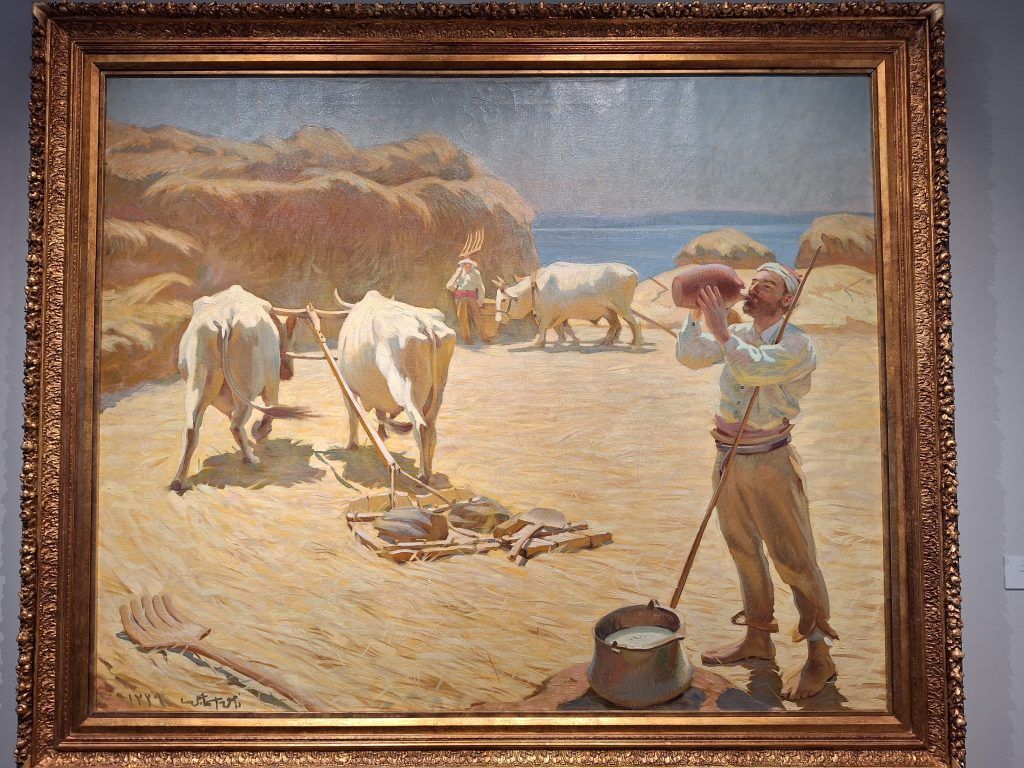

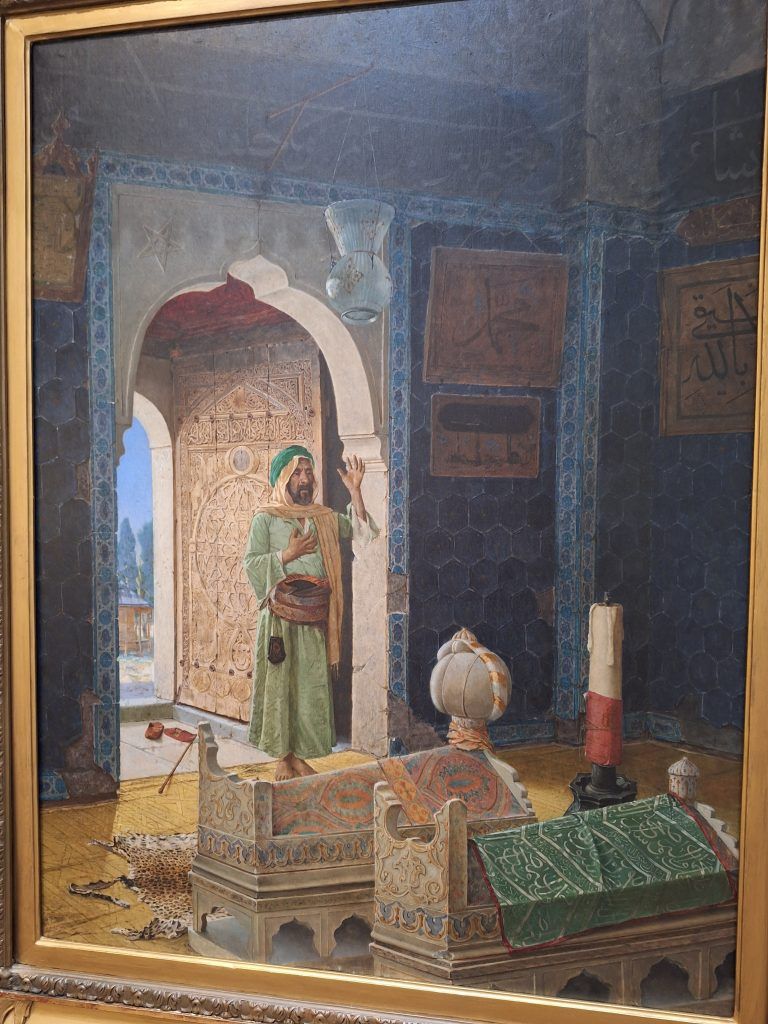

The Istanbul Museum of Painting and Sculpture just opened in September of 2022. The museum was originally housed in the mansion of the crown prince attached to the Dolmabahce Palace in the Besiktas neighbourhood of Istanbul. The building housing it dated back to 1856. On 20 September 1937, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Turkish Republic, suggested it be conversion into a museum since the imperial family had been driven into exile with the coming of the Turkish Republic.

It exhibits Turkish painting and sculpture from late Ottoman times through to modern times. As you can see below, many of these works are really good.

Galata Tower

The most prominent feature of the New District skyline is the 205 foot tall stone Galata Tower (sometimes called the Genoese Tower). It has been used over the centuries as a fortification, a fire tower, a barracks, a dungeon, and even as a launch pad to test the possibility of human-powered flight. In the Middle Ages, when Byzantines controlled the historic core of the city, they granted land concessions to their Italian trading partners to use for docks and warehouses. The Galata area was the territory of Genoa. The Genoese rebuilt this tower (once a lighthouse) in the mid-14th century as part of the fortifications of their colony.

On the Asia Side

The Asian side of the Bosphorus has long been home to small towns and villages, but today it consists mostly of modern sprawl. Development boomed here after the first bridge over the Bosphorus opened in 1973. While European Istanbul is known for its historic quarters and time-honored ways of life, Asian Istanbul boasts modern infrastructure, bigger homes, and the efficiencies of contemporary life.

In the Ottoman era, Uskudar was the gathering and departure place for pilgrims and caravans heading to Mecca, giving it a spiritual ambience that is still apparent today. Countless mosques and Sufi lodges were built here, attracting religious communities.

One of the many mosques in the area.

Celebrating 100 years of the Turkish Republic.

Some of the modern apartments overlooking the Bosphorus.

Suleyman’s Mosqe on the left across to the Galata Tower on the right.

Camlıca Tower is a 49 story telecommunications tower with observation decks and restaurants a few miles from the main Uskudar waterfront. The hill it’s on originally housed a gaggle of various telecom towers. The purpose of this structure was to consolidate all this and help modernize Istanbul’s telecom infrastructure. It offers some really nice views of Istanbul.

There is a lush park surrounding the tower where people can come for picnics.

The view across the first Bosphorus bridge to one of Istanbul’s main business districts.

The view across to the Old City.

A nice view of the newer architecture sprawling out on the Asian side.

The picturesque Camlica Mosque.

The historic Kadıkoy district predates even the Byzantine Empire. Settled in ancient times by Greek colonists, this area was known as Chalcedon. Dorian Greeks from Megara (near Athens) came here around the seventh century BC to access its vast, cultivable lands. And through the Byzantine and Ottoman periods, Chalcedon was the “bread basket” of the capital. Far from the city center, it also provided seclusion for Christian monasteries. Today’s Kadıkoy, with over a million people, is a modern commercial and residential district that has grown up around its ferry hub.

Looking across to the walls of Topkapi Palace.

The Surp Takavor Armenian Church dates back to the early 1700s and the current building was completed in 1936.

There’s a thriving market near the waterfront with all kinds of clothing and electronics stores on the outer rim and restaurants and traditional fish stalls in the center.

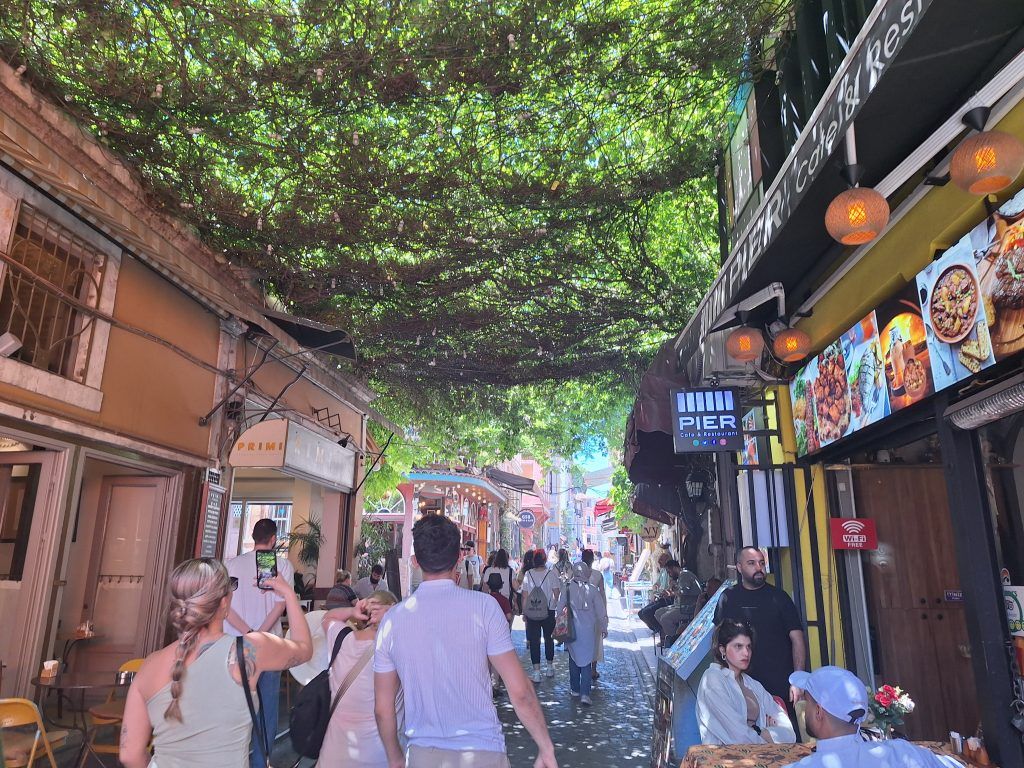

General Street Scenes

Here are just some general street scenes from walking around various parts of Istanbul.

I took one of the trams to the end of the line. It went through miles and miles of nondescript six to eight story apartment buildings, many with retail stores on the street level. I got a good sense of the sprawl of the Istanbul from this ride.

Turkish Experiences

A Turkish bath, or hamam, is a prominent feature in Turkish culture and was inherited from the model of the Roman thermae. I was originally going to go to a traditional hamam, but the ones I was recommended were either not near where I was staying or were in historic buildings that were extremely expensive. I ended getting the experience in a hotel spa that was near my apartment, received great reviews on Google Maps, and was reasonably priced.

The exprience was still pretty authentic. First I sat in a sauna for about 10 minutes before moving into a steam room for another 5 minutes to completely open my pores. Then the real fun began. I went into the traditional hamam room and lay face down, naked, on the heated marble slab pictured below. First the attendent poured hot water all over me. Then she took a towel wrapped in soap suds, wrung it out numerous times over me and I ended up being covered in a cloud of soap. After that she put on a rough glove and scrubbed every inch of my skin. To make up for that, more soap was added and I got a nice message with some more cleaning. Then I turned over and everything was repeated on my other side. While it was a great experience, it wasn’t sensual in any way. A Turkish delight is a type of candy, not a component of a full body scrub…lol!

A Turkish shave is a traditional shaving method that uses a bowl of water, a razor, soap and a hot towel. The first step of the process uses a hot towel to soften the beard hair and open the pores. The soap is then used to create a lather, which is applied to the beard and then the razor is used to shave the beard.

I went to a local Turkish barber and got my face and head shaved. One other component to his process was putting hot wax over my ears and on my nose. Once the wax cooled and dried, he pulled it off to remove any loose hairs. I understood why he did it on my ears, but couldn’t figure out why this was done on my nose. I’ve read they sometimes used burning stick to clear out your nose hairs, but thankfully he only used an electric clipper for that. It was a great experience, but it wasn’t cheap, so it was something I’m happy I did once.

A Turkish breakfast, or kahvalti, is one of the best components of a Turkish diet. It generally consists of black and green olives, cucumbers, cured meats, dips and sauces, eggs, fresh cheeses, fresh tomatoes, fresh-baked bread, fruit preserves and jams, honey, pastries, and sweet butter. I went to a small, local restaurant near my apartment and every morning I got this nicely modified kahvalti. There were no cured meats on the owner’s menu, but I did get him to add some eggs. It was a nice start to each day.

Airbnb Apartment

I stayed in an Airbnb near the Shishane metro stop which was on the top floor of a six story building. The views were amazing.

Unfortunately, there was no elevator. So I paid a price for these views by having to navigate six flights of narrow stairs.