I just got back from a weeklong trip to the Mexican states of Yucatan and Campeche to see three colonial cities and three large Mayan ruins sites. In this blogpost I’ll discuss my travels to the three ruins. In the previous, I discussed my visits to the cities.

The main theme for these three ruins, besides how stunning each is in its own way, is how confusing the information is for each right now in this Covid environment. All three re-opened up at various times in September as Covid restrictions continued to ease. There was fanfare as the most popular one, Chichen Itza opened. For the other two it was a lot less clear.

And then, once I was able to figure out that they were all opened, tropical storm Gamma and hurricane Delta came through last week. The roads to Uxmal and Chichen Itza were closed for a couple of days last week because of storm damage. Finally, last Saturday it appeared they were all opened and I made plans to leave the next day for this trip. I wanted to make sure I saw everything in case the Covid situation got worse again and they ended getting closed down.

But then I found out actually getting to the ruins from each city was also an adventure.

Chichen Itza

I arrived in Valladolid on Sunday afternoon and got information that a bus to Chichen would leave the next morning at 8:30 and I could catch an afternoon bus going back. When I arrived at the bus station that morning at 8:00 I was told there were no buses going to Chichen and that there was no other way to get there. The woman at the ticket counter felt that not even colectivos (inexpensive vans the locals use for relatively short trips) would be going. My heart sank.

I walked by a parking lot nearby that had some colectivos. None of them were going to Chichen, but one guy pointed me down the block. Success. I found a colectivo in another parking lot that was going. There were already people sitting in the van. One tall Mexican started talking to me in English. His name was Carlos and it turns out he has joint American and Mexican citizenship. He said there’s six of us now going and the driver is waiting for two more to get enough people to leave. They had already been waiting for 30 minutes. Time was going by. Carlos suggested we just pay the extra fair for two people and we could leave. Since that amounted to an additional $2, we both made that deal with the driver. The good news was, getting back was incredibly easy. Within 15 minutes of leaving the site, a colectivo going back to Valladolid showed up in the parking lot.

The trip was well worth it. Chichen Itza was magnificent. The main pyramid was amazing and all the other parts were extremely impressive, especially the 100 meter plus main ball court, which is considered to be the biggest one they’ve found out of all the Mayan ruins so far. There were a fair amount of tourists there and a ton of vendors as you walked from one ruin to another. I can’t imagine how crowded it would be during a normal tourist environment.

Lonely Plant provides a nice summary of its history:

Most archaeologists agree that the first major settlement at Chichén Itzá, during the late Classic period, was pure Maya. In about the 9th century, the city was largely abandoned for reasons unknown. It was resettled around the late 10th century, and shortly thereafter it is believed to have been invaded by the Toltecs, who had migrated from their central highlands capital of Tula, north of Mexico City. The bellicose Toltec culture was fused with that of the Maya, incorporating the cult of Quetzalcóatl (Kukulcán, in Maya). You will see images of both Chaac, the Maya rain god, and Quetzalcóatl, the plumed serpent, throughout the city. The substantial fusion of highland central Mexican and Puuc architectural styles makes Chichén unique among the Yucatán Peninsula’s ruins. The fabulous El Castillo and the Plataforma de Venus are outstanding architectural works built during the height of Toltec cultural input. The sanguinary Toltecs contributed more than their architectural skills to the Maya: they elevated human sacrifice to a near obsession, and there are numerous carvings of the bloody ritual in Chichén demonstrating this. After a Maya leader moved his political capital to Mayapán while keeping Chichén as his religious capital, Chichén Itzá fell into decline. Why it was subsequently abandoned in the 14th century is a mystery, but the once-great city remained the site of Maya pilgrimages for many years.

Uxmal

My transportation challenges continued in Uxmal. I was now in Merida. There were no buses going to Uxmal from Merida and I couldn’t find out where any colectivos might be leaving from. It got to the point that the woman at the bus ticket window thought Uxmal was actually closed. I walked outside the bus station and did some research on my phone. Nothing. So I went back into the ticket line and talked to someone different. He said I could take a bus to Muna leaving at 9am the next morning and then a colectivo from Muna to Uxmal. I bought the bus ticket. He also suggested there would be a bus around 3pm going by Uxmal that could take me back to Merida.

The next morning I got on the bus. When I got off in the small town of Muna, I asked a local about a collective to Uxmal. He said one would come by within an hour, but he didn’t know when. At that point, I walked over to a taxi driver and decided to take a relatively inexpensive taxi the short way to Uxmal.

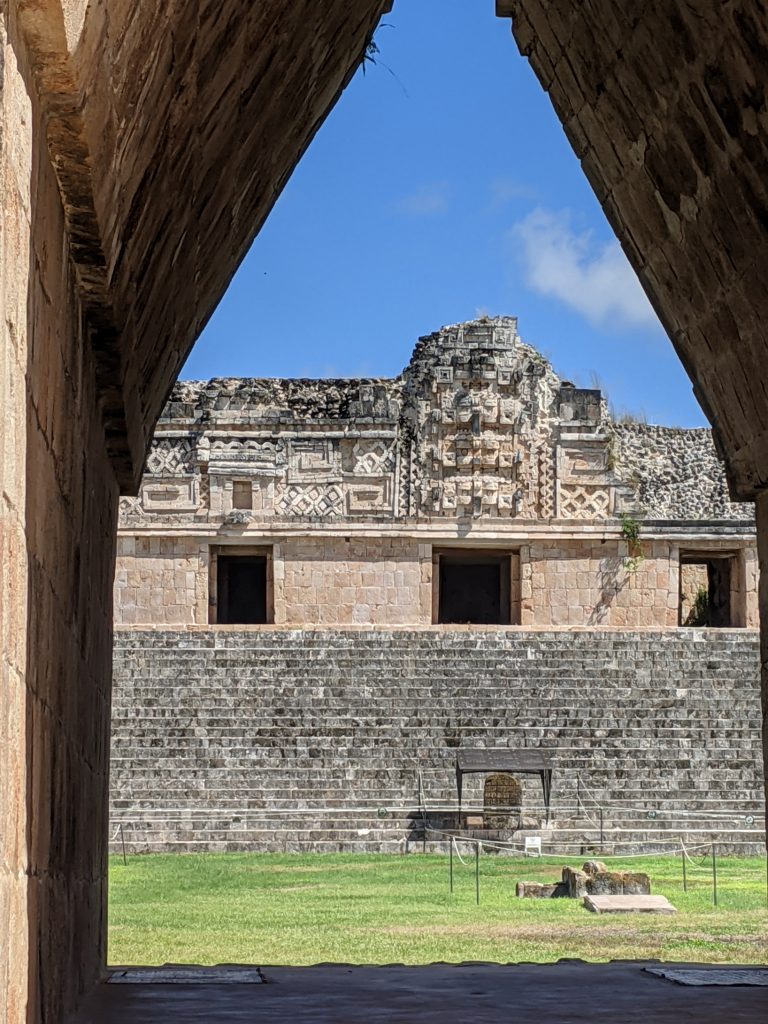

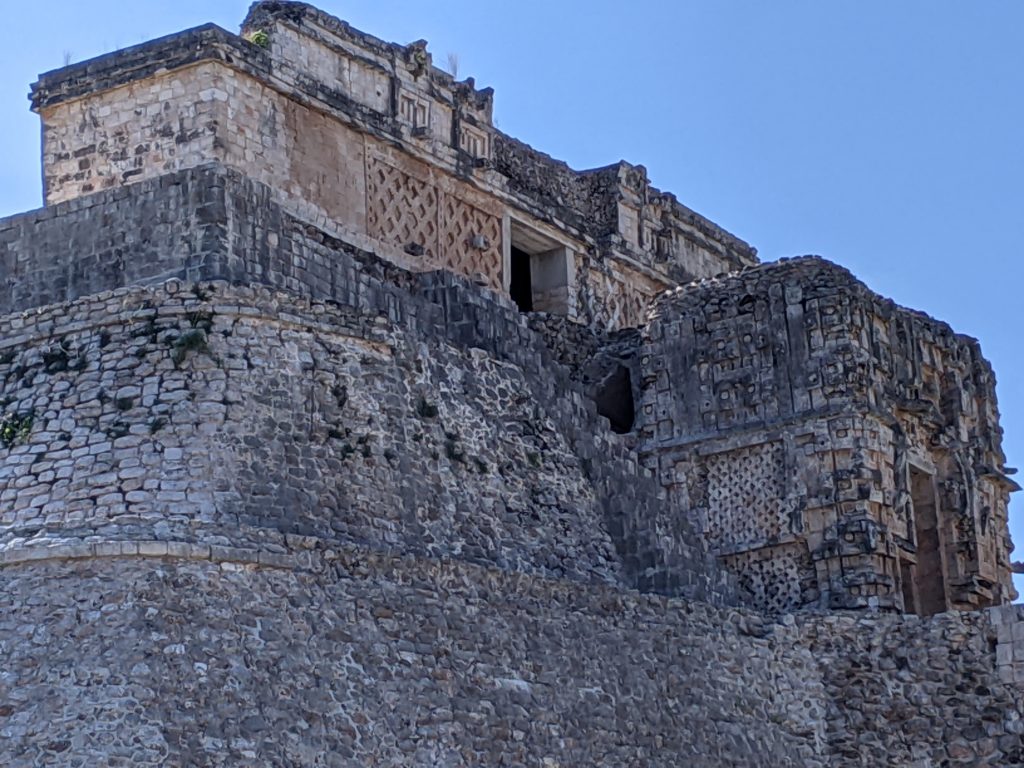

Again, the trip was worth it. Uxmal was even more enjoyable than Chichen Itza. There was less than 30 people in the whole park and there were no vendors. I was mostly by myself walking around. While the ruins weren’t of the scale of Chichen Itza they were still imposing in their own way and even more sublime in their styling and layout.

The Lonely Planet history:

Uxmal was an important city in a region that encompassed the satellite towns of Sayil, Kabah, Xlapak and Labná. Although Uxmal means ‘Thrice Built’ in Maya, it was actually constructed five times. That a sizable population flourished in this dry area is yet more testimony to the engineering skills of the Maya, who built a series of reservoirs and chultunes (cisterns) lined with lime mortar to catch and hold water during the dry season. First settled about AD 600, Uxmal was influenced by highland Mexico in its architecture, most likely through contact fostered by trade. This influence is reflected in the town’s serpent imagery, phallic symbols and columns. The well-proportioned Puuc architecture, with its intricate, geometric mosaics sweeping across the upper parts of elongated facades, was strongly influenced by the slightly earlier Río Bec and Chenes styles. The scarcity of water in the region meant that Chaac, the rain god or sky serpent, carried a lot of weight here. His image is ubiquitous at the site in the form of stucco masks protruding from facades and cornices. There is much speculation as to why Uxmal was abandoned in about AD 900; a severe drought may have forced the inhabitants to relocate. Rediscovered by archaeologists in the 19th century, Uxmal was first excavated in 1929 by Frans Blom. Although much has been restored, there is still a good deal to discover.

Now that I was at Uxmal, getting back proved to be as much of a challenge as getting there. When I walked into the park two different people told me there’d be a bus coming by the highway at noon and another one at 3pm. So I finished going through the ruins just after 11:30 and walked over to the spot on the highway. A woman at a small food truck confirmed that there’d be a bus soon and another in the afternoon. It was a pretty, shaded area by the road, so I didn’t think the wait would be too bad. I waited.

Noon came, no bus. 12:30 came no bus. 1pm came, no bus. I talked to the woman a couple times. She said with Covid and the lack of tourists sometimes only the 3pm bus comes by. I gave up. I walked back to the park to find a taxi. But I didn’t see any taxis in the parking lot. I walked back in with my ticket and asked someone who spoke English. He found one of the guides that didn’t have any work today that would be my taxi driver to make some extra money. The driver spoke really good English. He said that since a new road was built a year ago and with the lack of tourists recently, no buses came by anymore. This lack of clear information was amazing! Anyway, I got to Muna quickly and he put me at a spot where either a colectivo or bus would come by to Merida soon. Within 15 minutes I caught a bus back to Merida.

Edzna

Getting to Edzna proved to be much easier than getting to the other two ruins. From my research I had a general idea where to pick up a colectivo from Campeche. My Airbnb host confirmed that general part of town, which was nearby. The afternoon I arrived in Campeche I went to two different colectivo areas before I found the right one. I got everything confirmed and the process was incredibly easy the next morning.

And again, the trip was worth it. Edzna was not quite as impressive as Chichen Itza or Uxmal but it was still amazing. And it was basically empty. There was a lone traveler and a guide with three Mexican women most of the time I was there. As I left a few more people came in. The coolest part of Edzna was you could climb up most of the ruins. It was a fascinating site as it was composed of three squares with 4 buildings on each side, and the main one always on the east. There was a main square, a smaller, older square past that, and then you could climb up part of the east building on the smaller square and it ended up being a part of it’s own small square. I really enjoyed the short time I spent there.

Again, the Lonely Planet view of Edzna’s history:

Edzná’s massive complexes, which once covered more than 17 sq km, were built by a highly stratified society that flourished from about 600 BC to the 15th century AD. During that period the people of Edzná built more than 20 complexes in a melange of architectural styles, installing an ingenious network of water-collection and irrigation systems. (Though it’s a long way from such Puuc Hills sites as Uxmal and Kabah, some of the architecture here has elements of the Puuc style.) Most of the visible carvings date from AD 550 to 810. The causes leading to Edzná’s decline and gradual abandonment remain a mystery; the site remained unknown until its rediscovery by campesinos in 1906. Edzná means ‘House of the Itzáes,’ a reference to a predominant governing clan of Chontal Maya origin. Edzná’s rulers recorded significant events on stone stelae. Around 30 stelae have been discovered adorning the site’s principal temples; a handful are on display underneath a palapa just beyond the ticket office.